Kaden Cook was dying before he ever started living.

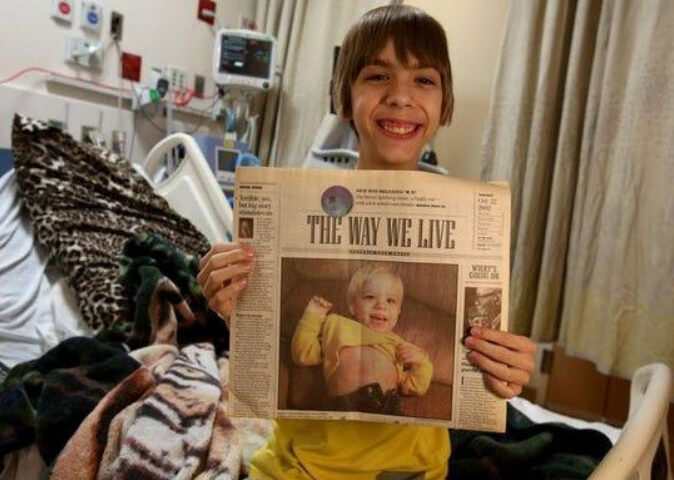

He was just 2 years old and had thick, fluffy blond hair and big green eyes that seemed to change color with the weather. He would glide around on his tiptoes, and when he pointed to the incision on his thigh, where a doctor had taken a muscle biopsy, trying to find out what caused the disease in his heart, he said ever so sweetly: “Who did dat?”

Doctors discovered that Kaden had cardiomyopathy, a rare heart disease, and needed a transplant or he was going to die.

Free Press photographer Eric Seals and I met Kaden in 2002. We produced a series of stories about him, trying to capture the hell of waiting for a heart transplant and what it was like after getting it.

It was a series that lasted just 17 years.

“We knew it was coming, but you are never ready,” his mother, Trishann Cook, said.

The funeral is Saturday.

“He wanted to be cremated and he wanted to have a tree of life,” Trishann said. “It’s like where you bury the ashes and plant it with a tree. He had the tree picked out that he wanted. It’s going to be planted at his dad’s place.”

Cats, Caramello and dogs

Before the transplant, we followed Kaden and his family to hospital visits and hung out with them at their home in Sault Ste. Marie.

We were in the operating room on the magical day, when Kaden got a new heart at C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital in Ann Arbor.

After the transplant, Kaden was given about 12 glorious years. He liked to fish, camp, swim, play video games, ride on a golf cart and spend time on his computer. He loved his cats, waffles and Caramello, and his dogs, Tido and Midas.

We published an update on the one-year anniversary of the heart transplant. Kaden, who was three-fingers old, was doing great. But his parents were struggling. The stress of waiting for the transplant had ripped apart their marriage and they eventually got divorced.

We published an update after his five-year anniversary. “Health-wise, he’s doing good,” Trishann said at the time. “He likes playing on computers and things like that.”

Kaden was taking five medicines: three anti-rejection drugs, one for high blood pressure and one for high cholesterol. “He’ll take anti-rejection drugs the rest of his life,” Trishann said.

Kaden went to Mott every six months for tests. His new heart was expected to last 10-15 years.

‘He knew it was coming’

But he started to slip about five years ago.

Doctors discovered Kaden had myofibrillar myopathy, a rare genetic disorder that saps the strength in his muscles.

His new heart was doing great, ironically enough, but his body was withering away. He could no longer run or go out to play. He barely could walk.

After the muscles in his neck started deteriorating, he had trouble swallowing, his weight dropped to 67 pounds. He needed a feeding tube.

“He was literally skin and bones,” Trishann said. “He was on that for a couple years and gained weight, but the muscles were still deteriorating.”

He lived with his father, Kevin. “His dad’s shop is right across the road,” Trishann said. “He’d leave work and spent countless hours with that boy, taking care of him.

“Kaden was getting weak. He could barely talk. I couldn’t hear him, plus he had the mask on all the time. He would write out things on the computer for me. He said, ‘It’s annoying, I can’t stay wake for more than 10 minutes at a time.’

“I feel like he knew it was coming. He spent the last 10 days, ’round the clock, in his wheelchair. He couldn’t get into bed alone. It was too painful to get into bed. He was sleeping in his wheelchair, at his computer desk, slumped over. That’s the only way he could sit for the last, I don’t know how long.”

He never let anybody know he was scared. He wouldn’t talk about dying.

“He had a mask that he was supposed to use for nighttime but he used it all day long for two or three years,” Trishann said. “He wouldn’t take it off. He couldn’t breathe without it. He was really bad at the end — terrible.”

The gift of time

“What will you remember?” I asked Trishann during a phone call Tuesday night. “Will you remember the 12 amazing years or the last five?”

“He was such a smart ass,” she said. “Always had something smart to say.”

Kaden always teased his mother for being clumsy, and that came to mind just a few days ago.

“I was walking outside to my truck on the phone with my sister, going to pick up my little one and I saw something shining under my truck,” she said. “I bent over to look at it and my feet went out from under me.”

And she is certain Kaden was watching from heaven.

“I sat up and went, ‘Kaden Chase, that’s not funny!’ ” she said, laughing. “I told the kids. His sister goes, ‘Oh, you know he’s laughing his butt off right now.’

“He was always making fun of me, saying I should get a fall risk bracelet.”

She laughed again.

“He was the strongest person I’ve ever known in my entire life,” Trishann said. “We all are here crying and want him back for selfish reasons because we miss him. We didn’t want to lose him. But not once did I see that boy cry. Right to the end, he was about protecting everybody else’s feelings, right to the bitter end.”

Kaden’s story showed the need for organ donation, and his life showed what can be gained — those 12 glorious years.

But there are nearly 2,800 Michigan residents still waiting for organ transplants.

Learn more about Gift of Life at www.giftoflifemichigan.org or call 1.866.500.5801.

Source: Detroit Free Press

- Laker Men’s Basketball Handle Kuyper 88-55 - December 23, 2024

- MYWAY Sault Bridge Brawl & NEMWA Regional Results - February 22, 2024

- Crawford County Prosecutor clears State Trooper in the fatal shooting of man earlier this month - February 23, 2023