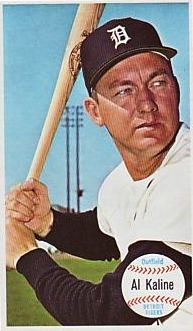

Al Kaline, who in a long and unique Detroit Tigers lifetime grew from youthful batting champion to Hall of Famer to distinguished elder statesman, died Monday afternoon at his home in Bloomfield Hills. He was 85.

A cause of death was not immediately available. John Morad, a close friend of the family, confirmed the news to the Free Press after speaking with Kaline’s younger son, Mike.

Kaline is survived by another son, Mark, and his wife, Madge Louise Hamilton.

In 22 seasons with the Tigers, most of them as a marvelous right fielder, Kaline played in more games and hit more homers than anyone else in club history, and he compiled a batting résumé second only to Ty Cobb’s.

But while Cobb was widely reviled for his bitterness and meanness, Kaline was eminently respected for his on-field elegance and off-field graciousness.

Thus, Kaline has a strong claim as the most distinguished Tiger of them all.

Albert William Kaline was born in a working poor section of Baltimore on Dec. 19, 1934. His father was a broom maker. His mother scrubbed floors. When Kaline received a reported $35,000 signing bonus from the Tigers in 1953, he paid off the mortgage on his parents’ home and paid for an eye operation for his mother.

“They’d always helped me,” he said. “They knew I wanted to be a major leaguer, and they did everything they could to give me time for baseball. I never had to take a paper route or work in a drugstore or anything.

“I just played ball.”

Kaline signed with the Tigers the morning after he graduated from high school — and made his major-league debut a week later. He would never play in the minors. He would never wear any uniform but Detroit’s.

Hall of Fame glove, bat

Kaline was 39 when he played his final game, in 1974. Days before his career ended, he had reached one of baseball’s most cherished plateaus when he recorded his 3,000th hit. But he finished with 399 home runs, and on the final day of his career he left the season-ending game with several innings remaining and thus lost a few at-bats in which he could have bid for the 400th homer.

But statistics never captured how special Kaline was. Like the Yankees’ Joe DiMaggio and the Cardinals’ Stan Musial, he embodied the beauty of the game and became a living monument of how gracefully it could be played.

Hall of Fame voters didn’t seem bothered that Kaline didn’t hit 400 homers. In his first year of eligibility, he was elected with 88% of the vote by baseball writers — well above the 75% required for induction. Yet the humble Kaline said he was “shocked” when he learned he had been elected. After the Hall of Fame’s initial class in 1936, only nine others before Kaline were elected in their first year on the ballot, a list of diamond luminaries that included Musial, Ted Williams, Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle and Jackie Robinson but not DiMaggio, Cy Young, Hank Greenberg or Yogi Berra.

Kaline is one of the few dozen players in baseball history to get 3,000 hits. Like his contemporary, Pittsburgh right fielder Roberto Clemente, Kaline is a member of the 3,000-hit club who is remembered nearly as much for his defense as for his offense — perhaps just as much. In one game as a rookie, Kaline threw out a Chicago White Sox runner for three consecutive innings — at home, third and second. The Sporting News said of a robbery he made in 1956 at Yankee Stadium: “No one who saw it will forget how Kaline shot above the right field scoreboard in the stadium to make a great one-handed catch on Mickey Mantle.”

Kaline is one of six Tigers with a statue behind the left-center field fence at Comerica Park. And despite his 3,007 hits and those club-record 399 homers, that statue shows him not with a bat in hand, but making a leaping, one-handed catch like the one he made on Mantle.

Yet without his defensive superiority, Kaline likely would have made the Hall of Fame on his hitting. Every eligible player who has gotten 3,000 hits has entered the Hall except for Rafael Palmeiro, whose candidacy was short-circuited by a positive test for steroids soon after his milestone base hit in 2005. Kaline won the American League batting title as a 20-year-old in 1955, and although he never won another batting title, he never stopped hitting.

In Kaline’s final season, ace Baltimore pitcher Jim Palmer said of him: “I like to watch him hit. I like to watch him hit even against us. He’s got good rhythm, a picture swing. Other hitters could learn a lot just by watching him. The thing about Kaline is that he’ll not only hit your mistakes, he’ll hit your good pitches, too.”

Palmer recalled how in his first big-league start, in 1965, he struck out Kaline looking on three pitches the first time he faced him. The second time up, Palmer said, he threw Kaline a fastball, curve and change-up. Kaline hit the change-up for a two-run homer.

After one year out of baseball following his retirement, Kaline joined the Tigers’ television team in 1976 as the analyst for play-by-play man George Kell, a former Tigers third baseman. Kell, also a Hall of Famer, and Kaline, after a rough learning curve, provided engaging, incisive commentary on Tigers telecasts for the next two decades. When Kell retired from broadcasting, Kaline worked on the air with play-by-play men Ernie Harwell and then Frank Beckmann into 2001.

Before the 2002 season, new club president Dave Dombrowski appointed Kaline a special assistant. He was a frequent inhabitant of the field and clubhouse throughout his 70s and 80s. After owner Mike Ilitch fired Dombrowski during the 2015 season, Kaline remained in the front office as a special assistant for the new general manager, Al Avila.

Short on a homer, long on humility

By never playing in the minors and wearing a Tigers uniform for every game, Kaline is in a very small group of players who performed for one team and one team only throughout his pro career. Another was a Hall of Fame contemporary, left-handed pitcher Sandy Koufax of the Dodgers. They faced each other twice, in All-Star Games in the 1960s, with Kaline singling and fouling out.

Baseball’s rules of the 1950s kept Kaline and Koufax out of the minors at the start of their careers. Back then, there wasn’t an amateur draft — the vehicle that gives one club exclusive signing rights to an amateur player. To keep down the bidding wars on amateur players in those predraft days, baseball mandated that any player signed for more than $4,000 would have to spend two years in the majors before he could be sent to the minors for seasoning.

The Tigers thought Kaline was well worth that possible inconvenience. When he came out of high school in Baltimore in 1953, the Tigers spread the word they had signed him for $35,000, a figure repeated countless times over the decades. However, in interviews for a 2010 book, “Al Kaline: A Biography of a Tigers Icon,” Kaline told author Jim Hawkins: “It was a $15,000 bonus, plus two years’ salary of $6,000 each, which was the major-league minimum at the time.”

Still, for a bonus worth $140,000 today, Kaline basically went straight from high school graduation to the Tigers. He was 18 years and six months old when he played his first game for them on June 25, 1953.

By the time Kaline became eligible to go to the minors in 1955, he was on the way to that season’s batting title. He was 20 years old when he finished that season with a .340 average, 21 points higher than anyone else in the league and 12 days younger than Tigers legend Ty Cobb was when he won the 1907 title. At 20 years and 280 days, Kaline remains the youngest batting champion in American League history.

Kaline’s highest finish in a batting race after that was second, which he achieved three times. He also twice placed third in the late 1960s. He never led the league in homers or runs batted in, and he never won its most valuable player award (he twice finished second and once third in the MVP voting).

But Kaline hit .300 or better in nine seasons, and he finished with a .297 lifetime average. In 10 seasons he won a Gold Glove as one of the three best defensive outfielders in the American League. In his later years, he played often at first base as well as in the outfield. In his final season, he served exclusively in a role that the AL had instituted the year before — designated hitter.

Kaline won the respect of the Boston outfielder who is widely regarded as the greatest hitter in history. This became evident one day as Kaline sat in the media dining room at Fenway Park before doing the telecast of a Tigers-Red Sox game. Into the room swooped Ted Williams. He knew his entrance would require him to fend off the Boston press with which he long feuded. But he had an important mission, as he growled at the reporters who approached him. “I just came in here to say hello to Al Kaline,” he said.

Boston wasn’t filled with such kindness for Kaline in 1967. In that season, he was selected an All-Star for the 13th straight year. But in the same season, he had a right to wonder whether he would be among the handful of all-time great players who never reached the World Series.

For the first several years of his career, Kaline and the rest of the American League basically were blocked from the World Series by a New York Yankees dynasty. Not only were those the days before the draft caused talent to be more equally distributed, they were the days before the major leagues were split into divisions. There were thus no postseason playoffs within the leagues; the teams that finished first in the American and National leagues advanced directly into the World Series.

In Kaline’s first 12 seasons, the Yankees won 10 pennants. Then the Yankees’ dynasty abruptly collapsed, and a few years later, in 1967, the Tigers made their first down-to-the-wire run at the pennant in Kaline’s career. They were eliminated when they lost their final game of the season. Boston — not Detroit — won its first pennant since the mid-1940s.

But the next year, 1968, the Tigers were not to be stopped, and they didn’t even need a huge season from Kaline. The team had a narrow first-place lead in the AL in late May when Kaline suffered a broken left forearm. When he returned five weeks later, the Tigers were well on their way to the pennant. They won it by 12 games with a 103-59 record. The MVP of the Tigers and the AL was right-hander Denny McLain, who became the first (and still only) pitcher to win 30 games in a season since the 1930s.

Typical of Kaline’s humility, he questioned whether he even deserved to be in the starting lineup for the World Series. He said he didn’t see how manager Mayo Smith could bench Mickey Stanley or Jim Northrup, who had gotten most of Kaline’s at-bats when he was injured. After his return July 1, they kept playing and Kaline logged only 191 at-bats. For the season, he started and finished only 58 games in right field. According to a Joe Falls exclusive in the Free Press the day after the pennant clincher, an emotional Kaline said, “I don’t deserve to play in the World Series.”

But with four outfielders for three starting spots, Smith came up with a daring solution for the World Series against St. Louis: He moved Stanley from center field to shortstop to replace light-hitting Ray Oyler, even though Stanley had played only nine games there in the big leagues. Kaline returned to right field for the World Series, and he batted .379 with eight RBIs. His 11 hits in the Series included two homers, two doubles and perhaps the biggest hit of the Series and of his career.

The Tigers were within a few innings of elimination when Kaline batted with the bases loaded and one out in the seventh inning of Game 5 at Tiger Stadium. He delivered a two-run single that turned a one-run deficit into a one-run lead. The Tigers never trailed again in the Series. They won Game 5, then went to St. Louis and beat the Cardinals in Games 6 and 7. At 33, Kaline had played on his first and only pennant winner and world champion.

In the following season, 1969, baseball expanded and went to divisional play. In 1972, Kaline played on a first-place finisher for the second and last time. Kaline, at age 37, got into one of the hottest hitting stretches of his career in the final days of the season and helped the Tigers edge Boston by a half-game for the East Division title. Over his last 10 games, eight of which the Tigers won, Kaline batted .512 (21-for-41) with four homers, eight RBIs and 15 runs scored.

If the Tigers had beaten Oakland in the playoffs, Kaline would have been back in the World Series. But in the winner-take-all final game of the playoff series, Oakland sneaked out of Tiger Stadium with a 2-1 victory. The potential tying run in the decisive Game 5 reached first base in the seventh, eighth and ninth innings against Vida Blue: Aurelio Rodriguez made the third out in the seventh, Kaline made the second out and Duke Sims the third out in the eighth, and Tony Taylor made the game’s final out.

Kaline’s 3,000th hit represented a major circle closing. It came in his hometown of Baltimore on Sept. 24, 1974. He had 2,999 hits when the game began. He grounded out in his first at-bat. In his second, he hit an opposite-field double down the right field line off left-hander Dave McNally for No. 3,000. “He hit a fastball that went right across the plate,” McNally said. “I got an autographed ball from him that day.”

Ten days later, on the final day of his career, Kaline’s humility surfaced again and perhaps cost him a chance at his 400th homer. There are a few accepted ways for a star to take his final bow: leave the field for a defensive replacement in the late innings or take a late-game at-bat. Either way, the crowd can give the departing stalwart one last resounding ovation.

Kaline chose neither route in his finale, which was played against Baltimore on a Wednesday afternoon in early October in front of a mere 4,671 at Tiger Stadium. He couldn’t take a final trot in from his defensive position because he was the DH, as he was every time he played that season. So his final appearance would come in the batter’s box.

Kaline had hits in 13 of his previous 15 games but he hadn’t homered since Sept. 18 off Boston’s Reggie Cleveland, his 13th of the season.

In his first two times up that day against the Orioles and left-hander Mike Cuellar, Kaline struck out looking and flied to left. His next turn at-bat came with two out and one on in the fifth inning. Instead, he allowed manager Ralph Houk to send up Ben Oglivie to hit for him against right-hander Wayne Garland.

The small gathering of fans was thus denied the chance to salute Kaline and to see him take a few more at-bats in pursuit of the 400th homer. According to one report, “the crowd booed thunderously.”

Afterward, Kaline explained that he had injured his left shoulder over the weekend, realized that he lacked the strength to hit a home run and asked Houk to remove him from the game. “I was sitting there in the clubhouse and I could hear them booing,” Kaline said. “I really felt sorry for Ben. It wasn’t his fault.”

Houk said: “With a hitter as great as he is, you don’t send him back out there when he says he’s had enough. I think I owed Al that much.”

Kaline’s early exit was so stunning, the fans’ reaction so overwhelming and the media’s coverage so negative toward the Tigers that Kaline still faced questions about it on the January 1980 day that he was elected to the Hall of Fame.

“That was one of my most embarrassing moments,” Kaline said years later. “But you have to understand that I didn’t realize at the time the fans came out to see me in my last time at-bat.”

Kaline made his permanent home in metro Detroit from early in his Tigers career. But in his later role as assistant to the president, he often went with the Tigers on their trips to Baltimore. In one such homecoming instance, he showed that he was anything but a front-runner. He joined the Tigers on their trip to Baltimore early in the 2003 season when they had a 4-25 record and already were being called one of the worst teams ever, which it turned out they were.

‘The best I ever played against’

When Kaline was 8, he was diagnosed with osteomyelitis and 2inches of bone were removed from his left foot. Despite a permanent deformity and constant pain throughout his life — “it’s like a toothache in the foot,” he once explained — Kaline quickly developed into a skilled athlete in a baseball-playing extended family.

Kaline was first a pitcher. That made sense, because his father and grandfather were catchers. “My grandfather was a bare-handed catcher in the old Eastern Shore League,” Kaline said on his first day in the big leagues. “And my father was an amateur catcher around Baltimore.”

Kaline recalled that when he was 12, he went 10-0 on his neighborhood team. But when he went out for his high school team as a freshman, his coach put him in the outfield because of his strong and accurate arm. “That was the best break I ever got,” Kaline said in 1955, the season he became a star.

Major-league scouts descended on Kaline’s high school games. The competition for him came down to the Tigers and a few other teams willing to make him “a bonus baby” — the player whose signing bonus was big enough that he had to spend those two years in the majors before he could go to the minors.

Early in his Detroit career, Kaline said, “I signed with the Tigers because they had shown the most interest and because I thought I might get a chance to play oftener with them.” In 1952, the Tigers had lost 104 games. In 1953, they lost 94 more.

In his first full season, 1954, Kaline took over as the Tigers’ right fielder. By mid-1955, when he became eligible to be sent to the minors, he was starting in the All-Star Game and was on the way to the batting title. Plus, his team finished with a winning record.

“Everything I hit that year fell in or was in the hole,” he said a quarter-century later. “That, and the pitchers didn’t start pitching me cute until August. In effect they were saying they’d rather take their chances with me and pitch around the big guys. Then they must have decided, ‘Hey, this guy’s for real.’”

When he broke Hank Greenberg’s club record for career homers, Kaline said, “How can anyone compare me with Greenberg? I’m not a home run hitter.” Kaline’s single-season high in homers was 29 — exactly half of the club-record 58 that Greenberg had swatted in 1938.

But consistent excellence is baseball’s greatest jewel, and Kaline delivered it for two decades. By 1970, his 17th full Tigers season, he noticed he was getting applause in parks throughout the American League. “This makes a guy feel good,” Kaline told The Sporting News. “Most of it is for being around so long. I’ve stood the test of time. And I haven’t done anything to embarrass the game or myself.”

The same can be said of Clemente, the Pirates’ star and humanitarian who died in a plane crash in the winter of 1972-73 while en route to help earthquake victims in Nicaragua. Like Kaline, Clemente broke in during the mid-1950s, played his whole career with one team and piled up 3,000 hits and innumerable defensive marvels. Upon Clemente’s death, Major League Baseball renamed in his honor its annual award for the player who “best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and the individual’s contribution to his team.”

In 1973, the first time it was given as the Roberto Clemente Award, the winner was Al Kaline.

While Clemente served in many ways as Kaline’s mirror image, Baltimore third baseman Brooks Robinson became his alter ego. Like Kaline, Robinson was a dangerous hitter who was one of the best defensive players ever at his position. And, like Kaline, Robinson continually presented a mix of class, competitiveness and humility.

In Kaline’s final season as a player, Robinson said: “When you talk about all-around ballplayers, I’d say Kaline is the best I ever played against. And he’s a super nice guy, too.

“There aren’t too many guys who are good ballplayers and nice guys, too. Your attitude determines how good you’re going to be — in life as well as in baseball. He’s got a great attitude.”

- Laker Men’s Basketball Handle Kuyper 88-55 - December 23, 2024

- MYWAY Sault Bridge Brawl & NEMWA Regional Results - February 22, 2024

- Crawford County Prosecutor clears State Trooper in the fatal shooting of man earlier this month - February 23, 2023