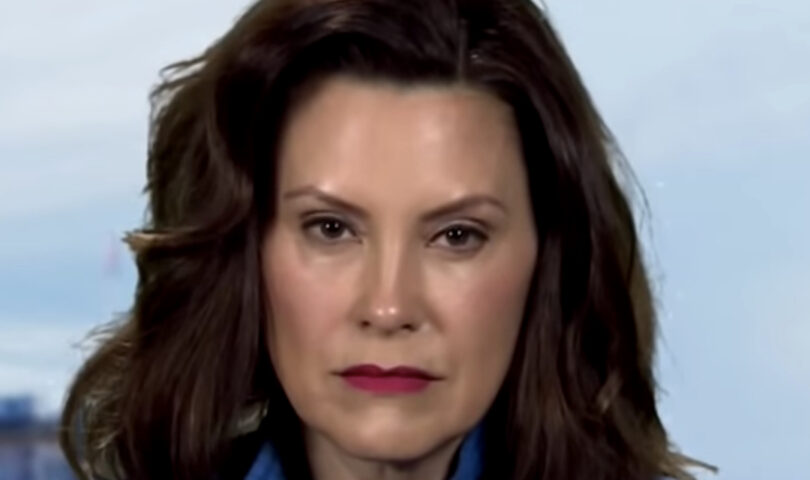

LANSING — Gretchen Whitmer stood on the floor of the Michigan Senate in 2013 and unloaded on a governor she claimed was operating in a “cloud of secrecy.”

Serving as Senate minority leader at the time, Whitmer lambasted then-Gov. Rick Snyder for convening a private “skunk works” commission to develop public school policies and criticized him for paying a top aide with money from a nonprofit that was not required to disclose donors.

Snyder’s “actions have been a far cry from the open and transparent governor he promised the people of Michigan that he would be,” Whitmer, a Democrat, said in a floor speech about the Republican governor.

Nearly eight years later, now in the third year of her own gubernatorial term, Whitmer is facing similar accusations from critics who say she has failed to live up to transparency pledges she made in her 2018 campaign.

Revelations of severance payouts and confidentiality agreements with former Health and Human Services Director Robert Gordon and former Unemployment insurance Agency Director Steve Gray have rocked Whitmer’s administration, which has spent the past year developing COVID-19 orders behind closed doors.

They are “don’t-say-anything, cover-things-up no-transparency-type contracts,” Sen. Jim Runestad, R-White Lake, said this week in a fiery speech outside the Michigan Capitol.

Gordon had signed several of Michigan’s most controversial COVID-19 orders, and Gray oversaw a department that struggled to pay claims and deter fraud when the pandemic cost hundreds of thousands of Michigan residents their jobs.

Both voluntarily resigned, according to statements at the time, and yet Gordon was paid $155,000 and Gray $86,000 in severance and settlement agreements that prohibit them from discussing circumstances that led to their departure.

“This is an unprecedented time where there’s no transparency in how (COVID-19) decisions are being made,” said Rep. Matt Hall, R-Marshall. “Because of that, the public doesn’t know how they were made” and now there is a former cabinet member “being paid not to talk.”

Calls for ‘sunshine’

Whitmer, whose office did not respond to a request for comment on this story, has stressed the importance of transparency repeatedly over the course of her political career.

As a candidate for governor in 2018, she released a 10-part “sunshine plan” she said would “make state government more open, transparent and accountable.”

Her plan called for tough new lobbying rules, personal financial disclosures by state employees, repeal of a controversial emergency manager law implemented by her predecessor and reversal of legislation that allows candidates to raise unlimited sums of money for super PACS that support them.

Whitmer hasn’t signed any of those proposals into law, but that’s not necessarily her fault: The Republican-led Legislature has not sent related legislation to her desk.

But as a candidate, Whitmer vowed to take matters into her own hands to enact one key reform: Subjecting her office to the kind of public records request rules that are required of state departments and local governments across the country.

Michigan is one of only two states that fully exempts both the governor’s office and legislators from its Freedom of Information Act, a distinction that has landed it on the bottom of national transparency and ethics rankings.

If the Legislature won’t act to change that, “I will use the governor’s authority under the Michigan State Constitution to extend FOIA to the Lieutenant Governor and Governor’s Offices,” Whitmer promised on her campaign website. “Michiganders should know when and what their governor is working on.”

But Whitmer has not voluntarily opened itself to public records requests. Her administration has offered support for legislation that would make some executive or legislative documents public, but those bills have not reached her desk.

The Michigan House Oversight Committee is expected to debate reintroduced legislation on Thursday, and Chairman Steve Johnson, R-Wayland, said he hopes the Whitmer administration’s use of confidential separation agreements will make transparency a more pressing issue for the Legislature this term.

“This situation has highlighted the need for this much-needed reform,” Johnson said.

He predicted both the House and Senate will “have the appetite” to approve the legislation this year and “make sure that the people in Michigan have transparency, that they can see what their government is doing for them.”

Whitmer championed transparency early in her tenure when she announced a series of executive directives that, among other things, required state employees to immediately report “any irregularity or discrepancy involving public money.”

Another directive sought to speed up state department responses to public records requests by limiting the use of extension periods, designating a “transparency liaison” within departments and encouraging all Freedom of Information Act requests to be fulfilled before their deadline.

“We are going to hold our government to the highest ethical standards that Michigan’s ever seen,” Whitmer said in a February 2019 speech to the Michigan Press Association.

But early in the pandemic, Whitmer temporarily gave state government more time to answer public records requests.

And overall, the FOIA process is still slow and cumbersome in Michigan, said Steve Delie, a transparency and open government expert at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a free market think tank based in Midland.

“I wouldn’t rate Gov Whitmer’s administration particularly favorably on this topic, but I wouldn’t rate just about any large public body favorably on this topic either,” Dellie said, noting the Mackinac Center has sued several governments and universities over Freedom of Information Act disputes.

Last year, the Mackinac Center successfully sued the Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs for the release of long-delayed documents related to complaints about businesses suspected of violating the governor’s COVID-19 orders.

And now, the nonprofit’s legal center is working with Detroit-area journalist Charlie LeDuff on a lawsuit to try and obtain aggregate nursing home death data the health department refused to provide, Delie said.

“There’s a general culture in Michigan that promotes a lack of transparency, and I think it’s a real problem, because the purpose of FOIA is to ensure free access to information,” he said.

“And what I’ve seen increasingly over the year, and certainly this last year, has been a real reluctance to release information in a timely manner, and when that information is released, it’s often so heavily redacted that any transparency purposes are kind of thwarted.”

‘No improprieties’

Asked Tuesday about the confidential separation agreement with Gordon, Whitmer appeared to initially read from a prepared statement, praising the former health director but saying she could not discuss details of his departure because of the confidentiality guarantee her administration had offered him.

Whitmer bristled at a reporter’s question about whether the payout amounted to “hush money,” saying Gordon and his team “were an incredibly important part of our response” to COVID-19 and that “there were no improprieties” with his work.”

“The nature of a separation agreement when someone in a leadership position leaves is that there are terms to it, and you can’t share every term to it,” Whitmer said.

That was a far cry from Whitmer’s calls for government transparency in 2014, when she requested an investigation and independent review of hiring and compensation practices in the Michigan Department of Treasury.

Snyder had kept former Treasurer Andy Dillon on the state payroll for two months after his resignation. But instead of aiding his successor’s transition in Lansing, Dillon was spotted on a Caribbean cruise.

“The governor needs to stop trying to cover this up and come clean about the sweetheart deals and cronyism that is rampant in the Department of Treasury,” Whitmer said at the time.

Whitmer’s own administration is now under fire for paying Gordon the equivalent of nine months salary as part of a deal that requires confidentiality.

Gray’s payout, also made with a confidentiality clause, amounted to more than six months of pay. He is still getting a check from the state after running a department that had been accused of withholding funds to thousands of jobless workers.

The two severances alone amount to $241,000 in taxpayer money and bar Gordon or Gray from discussing disputes or disagreements about two of the state’s most pressing policy issues of the past year.

A third state employee, former Gordon deputy Sarah Esty, got a separation deal from the state that paid her for one extra month of work but did require confidentiality.

Whitmer’s office hasn’t responded to Bridge Michigan requests about whether other officials received severance agreements.

Whitmer this week said separation deals are “used often” in both the public and private sector.

But experts and former officials told Bridge they are “not the norm” in government, where the confidentiality clauses give the appearance of impropriety, even if there is none.

“Concealment violates core civic norms of openness and transparency necessary to ensure government accountability. ”said Anthony Alfieri, director of the Center for Ethics and Public Service at the University of Miami School of Law.

State government should respect the privacy rights of employees in regards to things like personal health information, he said in an email to Bridge, but it’s inappropriate “to attempt to conceal possible or suspected misconduct by elected or appointed officials in labor and employment matters.”

Source: BridgeMI.com

- Laker Men’s Basketball Handle Kuyper 88-55 - December 23, 2024

- MYWAY Sault Bridge Brawl & NEMWA Regional Results - February 22, 2024

- Crawford County Prosecutor clears State Trooper in the fatal shooting of man earlier this month - February 23, 2023