Lynn Ordiway of Sault Ste. Marie described the early morning hours of June 26, 1986 when his life changed forever. He lived in Seymour, Tennessee at the time and was heading home on his motorcycle when a new tire came off the rim as he rounded a curve at a cliff with a 12’ drop-off leading to a rocky creek bed. Darkness hid imminent danger. It was only when he got off his motorcycle and stepped into oblivion that he knew he was in trouble.

“As soon as I fell, I knew my back was broken,” Lynn said. “Hours passed and I kept throwing rocks and sticks up to the highway in hopes of getting attention, either from a passing car or someone who might be walking. I had shortness of breath and was unaware my left lung had collapsed. In the pre-dawn hours, I was seeing flashes of white and a sky full of brilliant stars. I thought I might die. At one point, when I was looking up, a bright beam of light came down. Above me I heard a loud boom and saw a brighter light that slapped into the beam of light and went back up to the stars. I never saw God but I believe in passing, He gave me strength to hang on.

“When I saw the intense light, I was afraid but knew everything was going to be okay. Within a few seconds a man appeared on the road. He yelled ‘is anyone down there’ and when I answered I had been in the creek bed for three hours, he went for help. The ambulance was only a quarter mile away and the nearest hospital was only six miles. When I was finally rescued, I learned my T9 and T10 vertebrae were crushed. The emergency room doctors took one look at me and had me medivaced to Vanderbilt University for surgery where 18” steel rods were put in my back.

“The T9 and T10 vertebrae contain nerves and are true ‘ribs’ fused to the sternum. T9 connects to the kidney area. T10 innervates the muscles of the lower abdomen. With these damaged so severely, there was no hope I’d ever walk again. Once Vanderbilt did as much as they could, I was sent to Patricia Neal Rehab in Knoxville. I spent two months there learning how to sit and do other bodily functions. Then I was transferred to a rehab center in Smyrna, Tennessee that was better suited to meet my needs. I was trained there on all the things I needed to know about how to live with my new body.

“It was in Smyrna that I realized I was lucky to be a paraplegic. I saw every disability in that rehab center I could imagine. I met incredibly courageous people who refused to give up no matter what their physical bodies had suffered. The staff was encouraging, and slowly I conquered small skills that before my injuries would have seemed insignificant. To help me cope, I saw a psychologist. After my two-week evaluation, she said I had a high IQ and I laughed.

“My stay in Smyrna lasted four months. There was a lot I had to relearn in order to function on my own. As my body began to heal, I learned how to navigate the wheelchair and move from my bed to my chair. As a paralytic complete, it was necessary for me to develop a new daily routine. Simple things I learned as a toddler had to be taught in a new way if I was going to return home and live a productive life. With the support of the staff and the love of my family, I knew my life wasn’t over. It was just going to be different.”

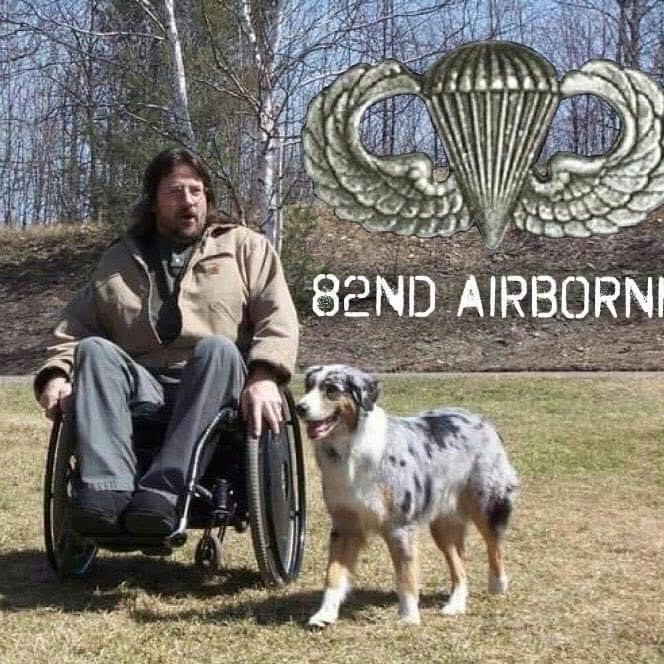

Lynn returned to his hometown of Sault Ste. Marie in 1987. Two years later he was driving a car with the aid of a portable hand control. He wasn’t going to let his disability deter him. As a youngster, he had always worked whatever job he could find. Then at 18, he drove dray wagons on Mackinac Island. At 19, he joined the U.S. Army and was in the 82nd Airborne from 1975-1982. After leaving the military, he worked logging jobs and drove truck until the motorcycle accident. When he came back to the Soo, he enrolled in LSSU for a semester, but it was too soon. “I needed to build up my stamina to navigate the wheelchair,” Lynn explained. “So I left college and turned to other pursuits.

“At one point, I was hired by Northstar Neon in the Soo. I worked there for about a year then decided to leave this area. I traveled to Dryden, Virginia where I learned to be a tube bender. Eventually I became an assistant instructor in a neon school. It was in Dryden that another physical problem occurred. To make me more comfortable while sitting in my wheelchair, there was a new device that emitted warm soothing heat. When I was home, the device malfunctioned and the heat came on. Since I could not feel physical pain, my left buttock was burned and I lost much bone and muscle. Healing took four months. Little did I know this episode that took place in 1999 was just the beginning of a long and painful journey.

“But before I explain about that, I’ll mention one of the most important things that gave me a new purpose in life. Prior to the motorcycle accident, I had a German shepherd named Chico. He was a pet but trained for obedience and guarding. Unfortunately, Chico passed away while I was rehabilitating. A few years after my accident, I realized a service dog would be a great help if it was properly trained. What I needed was a packer—a pick-up and pulling animal. Enter Shotgun, an eight weeks old shepherd. It took a year, but Shotgun was trained and was with me for seven years until I donated him to an Army buddy.

“I always had a knack for training dogs. My work with Shotgun was the beginning of a new and rewarding career. After Shotgun, I trained a Rottweiler named Cargo, then another Rottweiler called William Tell. Then came Zeb, a black Lab and after him there was Kit, an Australian shepherd. He was with me for 18 years and died on my birthday, June 4 in 2019. All these dogs were highly trained service or companion dogs personally trained by me. In Sault Ste. Marie, I became known as ‘Dogman’ and worked with animal shelters in Chippewa and Mackinac counties.

“Now I’ll backtrack to the burns from 1999. This is pretty graphic. The muscles from the flap surgery grew bone spurs that scrapped my hip and pelvic areas causing infection. I lost a hip and a lot of muscle that required four surgeries and 24 units of blood. I spent 11 months in a VA hospital in Milwaukee, almost six months at the VA in Ann Arbor, and three months at the Saginaw VA. I’m down to my last wound on the sacrum, a 1.2 cm x .5cm deep wound. By the time you read this, I’m hoping to be back at my Bruce Township cabin after spending two years in hospitals.

“Without the support and love of my family, it might be hard to endure all that’s happened to me, but family is everything. I’m thankful for my loved ones and grateful for their continued support and encouragement. My grandmother, Ursula Cryderman, was an amazingly resilient woman, and her daughter, my aunt, Theresa Rader, was also a strong role model who faced a lot of tragedy and loss. These women, as well as my mother, Mary Cobb, showed dignity and courage as they coped with catastrophes that could have brought grown men to their knees. When people ask me how I accept the health challenges I face, I credit my mother as well as my grandmother and aunt. Mom is still with us. The others are gone now, but they showed me that whatever life throws at you, you can get through it with the right attitude. I’ve always had an upbeat attitude and tried to turn a negative into a positive.”

Lynn said he’ll get another dog and begin training him as a service animal once he’s settled back in his own home. He already has a name picked out for his new companion, a black Lab he’ll call Buck. Never one to feel sorry for himself, Lynn prefers to have people focus on his dog instead of on him. Lynn recently returned home from a year’s stay at a VA facility in Milwaukee. This time everyone hopes he’s home for good.

- Saying Goodbye to Charlie Brown - July 2, 2024

- Mike Lynn Says Farewell to Lynn Auto Parts, Inc. - November 25, 2022

- Sharon Kennedy:The Hay Fields of Tony Jarvie - August 11, 2022