In 1923, Stanley Newton published, “The Story of Sault Ste. Marie and Chippewa County.” This is part five of a continuing series that tells the history of Sault Ste. Marie and area in its early years. – Laurie Davis

Schoolcraft Arrives on Steamer

It appears to have been overlooked by later chroniclers that the establishment of the British fort on Drummond’s Island was a direct cause for Governor Cass’s famous visit to the Sault in 1820, and the erection of Fort Brady two years later. The case is stated plainly in a note to Schoolcraft’s “Narrative of the Expedition to the Sources of the Mississippi.”

“We learn that the Indians are peaceable, but that the effect of the immense distribution of presents to them by the British authorities at Drummond’s Island has been evident upon their wishes and feelings. Upon the establishment of our posts and the judicious distribution of our small military force, must we rely, and not upon the disposition of the Indians. The important points of the country are now almost all occupied by our troops, and these points have been selected with great judgment. It is thought by the party, that the erection of a military work at the Sault is essential to our security in that quarter. It is the key to Lake Superior, and the Indians in its vicinity are more disaffected than any others upon the route. Their daily intercourse with Drummond’s Island leaves us no reason to doubt what are the means by which their feelings are excited and continued. The importance of this site, from a military point of view, has not escaped the observation of Mr. Calhoun and it was for this purpose that a treaty was directed to be held.”

Secretary of War John C. Calhoun had approved in 1819, the plan of Governor Cass to effect a treaty with the Indians at Sault Ste. Marie, to arrange for a Government military post at this place and to carry the flag of the United States into these remote northern regions, where it had never been borne by officials of the country. Henry R. Schoolcraft, then twenty-six years of age, accompanied this expedition in 1820 as a mineralogist and geologist.

Came Up River in Canoes

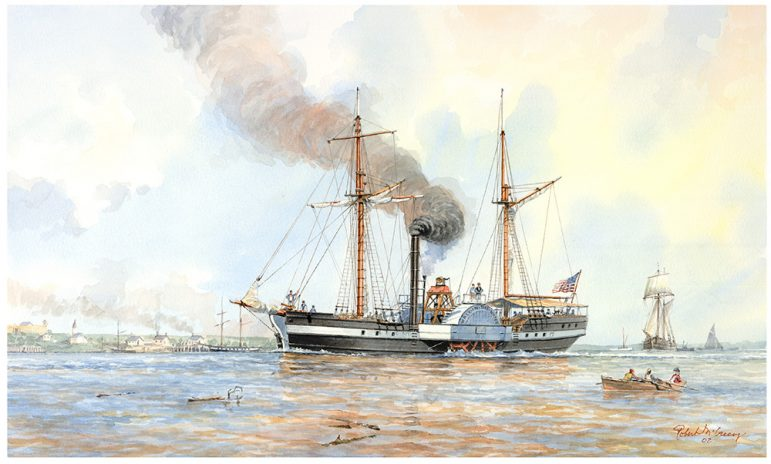

Schoolcraft came from Buffalo to Detroit on the steamer Walk-in-the-Water, the first vessel on the Great Lakes to use steam power, and which had been launched two years before. The Walk-in-the-Water had been as far north as Mackinac, but the Governor and his party preferred canoes for their trip up the lakes. In view, of possible hostilities, a squad of soldiers accompanied the Governor.

The expedition reached the Sault, on June 15th, 1820, landing as Schoolcraft says, in front of the old Nolan House, the ancient headquarters of the North West Company. This was probably the old home of Augustin Nolin, a French trapper and trader friendly to the American cause, who had retired and settled down in Sault Ste. Marie before the War of 1812, afterward selling his property to Mr. C.O. Ermantinger or his sons.

The party went into camp on the green beside the river, the hour being late, with soldiers on guard. The Indians, says Schoolcraft, occupied a high plateau in plain view several hundred yards west, with an intervening gully and a plain well-beaten footpath.

The visitors passed a quiet night in their tents, disturbed only by the sound of the falls and the distant monotonous thump of Indian drums. In the morning they explored the village and found it consisted of fifteen or twenty buildings occupied by the descendants of the original French settlers, all of whom drew their living from the fur trade. Most of the Frenchmen’s houses stood inside picket fences. All traces of the missionaries’ chapel had disappeared, but there was an old consecrated graveyard that was still used for interments.

The principal buildings of the village were those of John Johnston and the ones formerly occupied by the North West Company. Johnston was absent in Europe, but his family received the visitors hospitably and invited Governor Cass and his suite to take all their meals at the Johnston home. Schoolcraft was impressed, especially with the eldest daughter, Jane.

“The Sault Falls of St. Mary” continues Schoolcraft, “is the head of navigation for vessels on the lakes, and has been from early days a thoroughfare for the Indian trade. It is equally renowned for its white fish, which are taken in the rapids in a scoop net. The abundance and excellence of these fish have been the praise of all travelers from the earliest date and constitute a ready means of subsistence for the Indians who congregate here.”

“The place was chiefly memorable on our tour, however, as the seat of the Chippewa power. To adjust the relations of the tribe of the United States, a council was convened with the Chiefs on the day following our arrival.”

To this council, the Chiefs came clothed in their best and arrayed in feathers and British medals. Greeting the Governor with great dignity at his tent, they were seated and the pipes were smoked. Cass then explained to them through his interpreter, the views of the Government. He told them that he had come to remind them of the cession of the country by their ancestors to the French, to whose national rights and prerogatives the Americans had succeeded, and to secure their assent to its re-occupancy.

The Chiefs split on this proposition, some saying they knew nothing of such former grants, and others appearing to favor a settlement on the basis broached by the Governor, provided it was not intended to occupy the Sault with a garrison. They said, in the symbolic language of the Indians, that they were afraid their young men might kill the cattle of the garrison.

The Governor, being fully aware of their meaning, replied that sure as the sun then ascending would set, so sure would there be an American garrison at Sault Ste. Marie, whether they renewed the grant or not.

The principal Chief Shingabawossin was inclined to be moderate and said little. But Shingwauk, the Little Pine, who had conducted the last war party of Indians from the village in 1814, was openly hostile. So, too, was Sassaba, a tall chief in scarlet, whose brother had been killed by the Americans in the Battle of the Thames. He furiously drove his spear into the ground before him and delivered an impassioned oration in dissent. At its close he kicked away the presents brought by the expedition for the Indians and strode from the tent and the other Chiefs followed him.

The Indians went to their hill and scarcely had the whites returned to their tents when it was announced that the Saulteurs had raised the British flag in their camp. Trouble seemed certain and Governor Cass ordered his men under arms. Calling his interpreter and ordering the others back, the Governor did a most courageous thing. Proceeding up the path and across the ravine, he reached the lodge of Sassaba, before whose door the flag had been raised, and immediately pulled down the banner. Then he entered the lodge with the interpreter and informed the Chief that he had been guilty of an indignity and that if any other flag than the Stars and Stripes were raised there again, the United States would set a strong foot upon the Saulteurs’ rock and crush them. Finally the Governor, unmolested, brought the captured flag to his tent.

They sent their women and children across the river at once, but the whites waited in vain for the war-whoop. While the Chippewas doubtingly deliberated, Mrs. Johnston, the daughter of Waub-ojeeg, sought council with the Chiefs and told them their meditated scheme of resistance to the Americans was madness, that the day for such resistance had passed, that Cass was her guest, that he had the air of a great man, and could carry his flag through the country.

The advice prevailed, and she had the seconding of Shingabowassin and the Little Pine. Negotiations were renewed, and another council was convened in one of the Johnston buildings. Here the treaty desired by the Governor was amicably discussed and signed by all the Chiefs save Sassaba, June 16th, a treaty by which the Chippewas ceded to the United States a piece of land four miles square, fronting the rapids and lying within the present limits of Sault Ste. Marie. The Indians reserved the perpetual right to fish in the rapids. The consideration for this accession was paid on the spot in merchandise.

Such, in substance, is Schoolcraft’s account of the lowering of the British flag by Governor Cass, at the rapids in June 1820, in all likelihood on the identical spot where St. Lusson had raised the French ensign in the same month one hundred forty-nine years before. It is regrettable that the exact location of these historic occurrences is open to doubt. Many an argument, has been waged on this point of location, the opinion being advanced by some, and not without reason, that Sassaba’s flag stood on the high ground just south of the Weitzel Lock.

Schoolcraft mentions a ravine, which still exists near the foot of Bingham Avenue, and which in former times extended southward across the present line of Portage Avenue. But he does not say how far west of the ravine Sassaba’s lodge and the Indian village were placed, or at what distance east of it the Governor’s tent was pitched. He tells us the Indians “occupied a high plateau, in plain view, several hundred yards west of the expedition’s tents, with an intervening gully, and a plain, well-beat footpath.

- Memorial Erected - September 15, 2025

- Clergue Welcomed Back - August 24, 2025

- New Fort Brady Barracks 1908 - July 27, 2025