In 1923, Stanley Newton published, “The Story of Sault Ste. Marie and Chippewa County.” This is part ten of a continuing series that tells the history of Sault Ste. Marie and area in its early years. I have left punctuation and grammar intact. – Laurie Davis

Congress had enacted in 1816 that British traders and capital should be excluded from the American lines west of St. Mary’s River and along the boundary through Lake Superior to the Lake of the Woods. John Jacob Astor had bought from the North West Company all the posts and factories of that concern situated in the northwest, which were on the American side. These he incorporated with the American Fur Company, placing Ramsay Crooks and Robert Stuart in charge. The factors, clerks, and field personnel remained about as they had been under the North West Company, and the very thin diffusion of American principles among both traders and Indians made it difficult for the United States Indian Agents to supervise this business and to locate and seize the contraband liquors constantly filtering through.

When the Treaty of Prairie du Chien was negotiated by the Government with various tribes in 1825, a number of Saulteur Chippewas were present. The Saulteurs and others had complained that the true reason for the Commissioners of the United States Government speaking against the use of ardent spirits by the Indians, and refusing to give them, was not a sense of its bad effects so much as the fear of the expense.

The Joke Didn’t Take Well

To show the Indians that the government was above such petty principles, The Commissioners, General Clark, and Governor Cass, placed on the grass a long row of tin camp kettles, each holding several gallons of whiskey. After suitable remarks, each kettle was emptied on the ground in the Indians’ presence. “The thing was evidently ill-relished by the Indians,” says the narrator, “for they loved whisky better than the joke.”

Robert Stuart, Agent of the American Fur Company at Mackinac and himself a teetotaler, regularly obtained permits at Washington to bring into this territory a certain quantity of liquors each year. His statements were that the clerks and fieldmen of the Company were not inclined to take out whisky under these permits, but that the attitude of their opponents made it necessary. Their opponents, of course, were the men of the Hudson’s Bay Company, who still dispensed whisky north and east of the boundary line, and probably smuggled a good deal of it across. The Government Indian Agents were constantly troubled with the liquor question, and when they resorted for relief to the early courts, they generally found the juries against them.

It appears the American Fur Company felt that there would be more efficient hunting and trapping if the Indians could be kept sober and if liquor could be rigidly excluded. But it was considered also that the trade of the Company would suffer if some whisky were not furnished. Thus the illicit traffic was condoned to some degree, to the disgust of the Indian Agents and the detriment of the Indians. The traders and citizens generally, on both sides of the frontier, were leagued apparently in their supposed interest to break down or to evade the Congressional and Territorial laws which excluded liquors and made it an offense to sell or to give them,

Fur Trade Mightily Important

No one can read the early records of Sault Ste. Marie without being impressed with the enormous importance of the fur trade. The trade gave the Indians a market for the products of the forest, and without it, they would have wanted for many necessaries. But while it stimulated hunting, and to a certain degree, industry in the Indian race, it tended directly to diminish the animals upon which they subsisted and thus hastened the decline of their supremacy. And that supremacy was further neutralized of course by the trade in whisky.

With the coming of Colonel Brady and his troops to Sault Ste. Marie in 1822, the paramountcy of the Saulteur Chippewas in this vicinity ended, precisely two hundred years after Etienne Brule landed at the rapids. The French had had their long day here, and the British their short one. American civilization formally took up the work of developing the Sault and the north country.

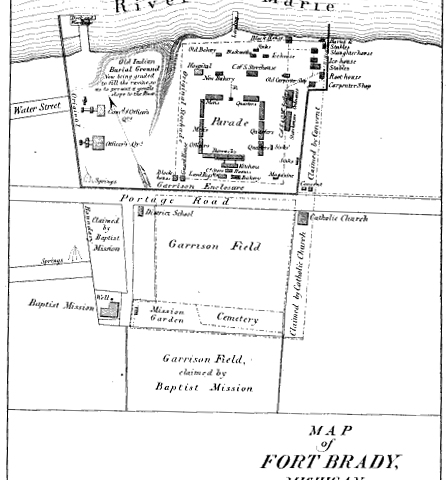

The troops occupied the Nolin enclosure east of the Johnston home during the winter of 1822-3, and April 19th of the latter year, they began to set up the pickets for a stockade or fort to which the name of Brady was given, in honor of the commanding officer. The pickets were cut in the vicinity of the fort, and timbers for block houses and the buildings within the stockade were brought from the Butte de Terre, or hill south of the village. A road was cut by the soldiers from the cantonment to this hill, and the greater part of this road is now Ashmun Street. Old maps made about twenty years later show only Ashmun Street (then called Ashman) extending southward as far as the hill; Bingham Avenue, the nearest north and south road to the fort location, reaching only as far as the present line of Spruce Street and being known then as Church Street.

The post office or federal building in the square bounded by Portage Avenue, Brady Street, Bingham Avenue, and Water Street, stands upon ground once occupied by the Fort Brady enclosure. The Whelpley map of 1854, gives the dimensions of the stockade in chains and links, the walls on the east and west sides being approximately 600 feet in length, and on the north and south sides 500 feet. Blockhouses of heavy timber were erected on the southwest and northeast corners, extending beyond the walls and placing the latter under crossfire, half the stockade being commanded by each block.

The south face of the southwest blockhouse has been marked by two small quadrangular stones extending a few inches above the surface of the ground, and almost hidden by the barberry hedge in front of the post office. They are a few feet west of the Portage Avenue entrance to the west door of the building. The line of the south wall may be discerned a few feet north of Portage Avenue, the same being marked “LINE OF STOCKADE,” in the cement walk which leads from Portage Avenue to the employee’s entrance to the post office. It is not known that any other extensions of the stockade have been marked.

The south line reached from the above blockhouse markers along the indicated line of stockade across Brady Street to a point in the present Baraga Schoolyard; thence the wall extended in a northerly direction to and a little beyond the brow of the hill abutting on Brady Field, the latter, of course, having been underwater at that time; thence west to a point a little east of the semi-centennial monument; thence south across Water Street to the place of beginning.

Stockade Made of Cedar Posts

The stockade was made of cedar posts about eight inches in diameter and eight feet in the clear, placed close together, and set firmly into the ground. The top of each post was sharpened to a point, and at convenient distances in the walls and blockhouses loopholes were cut for observation and firing purposes.

Within the stockade log and hewn timber buildings were erected for the garrison, a headquarters building, officers’ and men’s quarters, sick bay, bakery, and others, and there was a fairly commodious parade ground. South of the stockade was the fort garden, and beyond that the cemetery of the post. The foundation of the northeast blockhouse was at the river’s edge, not in the river, and water could be procured without going outside the palisade. When Commissioner Thomas L. McKenney came in July 1926, he found the north pickets of the stockade awash in the stream.

If, as nearly as can be determined, the Jesuit missionaries’ chapel was on the present site of Dr. F. J. Moloney’s home, the west line of the stockade, extended a hundred feet or so east of that location, and the fort walls probably included the plot of ground which was once the missionaries’ garden. The eastern palisade of old Fort Brady crossed the grounds of the old French Fort of de Repentigny at Water Street.

Before the fort buildings were erected, Henry Schoolcraft acted as librarian for the post, keeping the books at the Indian Agency. He relinquished this office to Lieut. S. B. Griswold on the erection of the fort. The coming of so many whites necessitated the establishment of a post office and upon Schoolcraft’s recommendation to the Postmaster General, Lieut. Griswold was appointed and served as the first postmaster of Sault Ste. Marie.

- The Immigration Service - January 22, 2026

- Millions Now Living Will See It - December 19, 2025

- Some Traffic Figures - November 20, 2025